Major Moment

in Digital Printing

Pixel Population

Games

When digital cameras passed the 5MP threshold,

desktop printers silently entered into a new era.

At football games, sometimes sections of

the audience hold up colored panels to make stadium sized pixel-based

graphics. A big image made this way might have 64x80 pixels,

but the result is kinda rough, but always fun.

Mosaic tiles in Ancient Rome had thousands

of spots of color and covered entire floors and walls. But they

were far from photographic.

At 1.2 megapixels (MP), images had 960

rows with 1280 columns of color spots making their images, and

at 160 ink-jet spots of color per running inch of paper, those

images could stretch to nearly 8x10 print size for crowd-pleasing

results.

A 5MP camera has more color spots than

the entire native population of Denmark, and if they all gathered

to do the stadium image trick, the picture they'd make would

be entirely photographically believable.

With over 6MP, the Digital Rebel has more

color spots than there are people in Bangkok, and the Canon 20D

with 8.2MP would need every soul in Austria to hold up a color

panel for its stadium picture. Seen from high altitude on a clear

day, such improbable displays would appear amazingly high in

resolution and detail.

The point here is that modern digital cameras

produce a huge number of color spots and placing them on a print

is a unique digital-era specialty. Good color printers cost as

little as $60 these days, and they squirt out letter page pictures

that pass for photographs quite easily. Better printers cost

more and offer extra features, smaller ink spots and novel input

options, but once you have reached satisfaction with letter page

results, the party has maxxed out. The only place left to go

is up. In size.

Canon's

i9900 printer has carved out a special place in the hearts and

minds of digital photographers --and even hold-out film photographers--

everywhere. The reason for that has to do with its sheer image

quality and performance. It's fast, silent, easy to work with,

and the pictures it produces are beyond criticism.

Canon's

i9900 printer has carved out a special place in the hearts and

minds of digital photographers --and even hold-out film photographers--

everywhere. The reason for that has to do with its sheer image

quality and performance. It's fast, silent, easy to work with,

and the pictures it produces are beyond criticism.

Assuming that your original file is in

good shape with all its colors and contrasts in the right places,

the i9900 will spit it out in short order at photographic maximum

quality on a wide variety of paper types and surfaces within

moments of your pressing the Print button. At up to 13 x 19 inches

(A3+ size) borderless images slide out of its platen in as quick

as three minutes. Mere letter page prints issue in just under

90 seconds. My personal favorite image/paper combo of a 9 x 6

inch image floating in a sea of white letter paper jumps out

of the machine in under a minute.

A lot of this speed comes from the sheer

squirt-count of its print head. With 6144 nozzles jetting out

ink droplets in the 2-picoliter range, each pass of the print

head achieves a significant addition of coverage to the page.

Here, Spot!

See Spot Run!

At the micro scale, the i9900 printer is

able to deliver 4800 x 2400 spits of ink per square inch on the

paper, but that is meaningless in terms of visual impact. It

means the printer has 4800 x 2400 opportunities per square

inch to deliver a precisely placed spot of color, not that each

spot is a perfect pixel.

You simply can't see a spot of ink 1/4800th

of an inch in diameter (they're roughly round), but you can see

the effect of 32 x 16 of them dithered inside an area about 1/150th

of an inch square. At this scale, every pixel from a Digital

Rebel would make a print 20.5 inches wide. A similar print from

a 20D camera would be 23.3 inches wide, and every original camera

pixel would be accurately portrayed via the dot count of every

color inside that tiny tile of color. Since no printer dot screen

would be part of the image, your eye would see only photographic

realism at this scale.

In mechanical printing, screen dots are

almost always 175 to the inch or coarser. Newspapers often print

them at 80 to the inch and some magazines limit their reproduction

screens to 133 per inch. National Geographic's rotogravure process

only uses 175 true ink dots per inch, but their size is tightly

controlled, giving the illusion of continuous tones and color.

Where this gains significance is in understanding that where

NGS prints one dot of ink, the i9900 is able to define 376 ink-jet

spurts per ink color, capable of defining chroma, tonality and

even some degree of image contour (if given a large enough file).

Non-Pixels

Ink spots aren't pixels. The printer DPI

you read about has nothing --repeat: Nothing-- to do with the

pixel count of your image. Printers take the pixel data from

your shot, then re-interpret the color of each pixel into a formula

of ink spurts that will add up to the color being portrayed in

the viewer's eye. To do that, Cyan, Magenta and Yellow inks are

used to deliver color, plus black ink to deliver extra tonality

and contrast. A few printers avoid using the black ink, but that's

only possible if the printer is designed to pile on enough CMY

ink at a given location, since all three of those colors do in

fact add up to black if they're dense enough on the paper. HP

printers do this, but it takes more ink to saturate the paper

this deeply.

Gamut Limuts

The color gamut (maximum range) of CMY

ink is limited. So is the color range on the color monitor you're

reading this from. So is the color range of film, photographic

paper and oil paint. It's a fact of life, but it doesn't have

to be as small as one might assume if more colors of ink were

available.

For instance: the greenest Green one can

make by adding 100% yellow and 100% cyan together on the paper

defines the green limit of the color gamut from those inks. But

one can formulate a greener ink that isn't made out of yellow

and cyan ink mixed together. It would have to be be created from

a different dye molecule, but it would be notably purer and livelier

to your eye.

The same holds true for Red, Blue, Purple

and Orange. If you had a hundred ink colors, the visual gamut

of a print could be quite superior to anything seen before, but

print time would rise phenomenally.

I have wondered aloud in my writings why

printers didn't have more than the standard range of ink colors.

Then three years ago printers began appearing with two extra

colors of light magenta and light cyan ink to assist in their

portrayal of delicate colors. Since ink-jet printers make their

images with blobs of ink sprayed statistically pseudo-randomly

on the paper (in what is called a stochastic array), light

areas of color can end up looking rather grainy if full strength

cyan or magenta ink were the printer's only option.

Making the spots smaller than eye resolution

is the first defense against looking gritty, and Canon has made

printer spurts as small as 2-picoliters each, meaning that they

are ONE 500 BILLIONTH of a liter each. Just to put that into

perspective, if you had 500 billion ping pong balls, it would

make a cube nearly half a mile on each side. Now crank up your

imagination and visualize that cube next to one single ping pong

ball. Yes, it's a very small spot, indeed.

Adding the light versions of C and M ink

lets the printer put dots onto the paper that aren't so far apart

that you can see them when looking extremely closely. That's

fine for hiding the dot pattern from your eye and making color

look smoother, but it does nothing to increase the color gamut.

So Canon has added two novel extra colors

into the mix, Green and Red ink. By analyzing the incoming RGB

image, the printer's internal processor can see the pure green

and red areas clearly. So it diverts some of the G and R ink

into those places, improving the color gamut about 60%. You might

not know this when looking at a print, but if you printed the

same shot on another printer, it would lack the particular snap

that the Canon i9900 delivers in its greens and reds.

Eight inks in all. CMY and K (black) plus

Light C and Light M, and the gamut-increasing G and R each come

in a separate ink tank, to be replaced as needed. Each color

costs about $11 US.

Setup

In my office there isn't space for many

extra items. The next room has more free area, so I decided to

put the i9900 there. Fortunately I use Mac computers, and that

means I could employ the Macintosh Airport Express as my printer

connection.

Lemme 'splain: The Airport Express is a

$125 wireless module with a USB outlet that can act as a wireless,

remote USB connection within about 50 feet of the local Airport

wireless network. It's a talented product with many more uses

than that, but for this test setup it proved ideal. Within mere

moments, I had hooked up the i9900 thirty feet away from my printer

and printed a test page.

Three input ports on the back allow USB

1.1, 2.0 and FireWire connections for data input. A separate

PictBridge USB connector on the front of the printer allows Canon

digital cameras to print directly, and that's a whole interesting

option you Digital Rebel and 20D camera owners can discover on

your own.

While Airport Express shoots data out its

USB port at USB 2.0 speed, it also accommodates USB 1.1 devices

without a whimper, so it can be plugged into either USB jack

on the i9900. Canon recognized that USB 2.0 protocols as distributed

by Microsoft with Windows XP created a Big Hairy Problem since

Microsoft's XP compatibility with USB 2.0 ports isn't totally

congenial, so they limited the data rate to USB 1.1 on one of

the two USB ports, thus making everybody sane. For the fastest

results, the FireWire plug on the back can be used by Mac computers.

Print Q

Since the printer was now on the LAN (Local

Area Network) every computer in the house could play. Canon's

printer drivers (now version 2.5.1 up from the 2.5.0 shipped

in the box) recognized the printer immediately, and everything

from spreadsheets to giant prints ran into it from every corner.

It even sorted out print jobs coming in from more than one computer

at a time.

Plain paper can be loaded in the single

vertical back tray with ease up to about 30 sheets at a time.

For photographic thick papers Canon recommends limiting the stack

to about 10 sheets. Paper can be from 4x6 to 13x19 but the absolute

maximum is slightly larger, about 13.25x23.4 inches. In order

to enjoy that upper limit, you would have to cut custom sizes,

but it's nice to know that it is doable.

Prints can be borderless, filling the paper

utterly and many custom settings are available to tweak the output

for various media. We found that many photographic paper types

were usable including some old glossy formulas that we had given

up on from the deep past. While other printers (some from HP

and Epson) couldn't use the older media due to ink drying, smearing

and crossover smudging failures, the Canon passed it with flying

colors and stable results.

Canon's own glossy giant paper is rather

expensive. At around $2.25 per sheet, it isn't something you

want to use for test printing, so using smaller media is recommended

for testing, then scaling the print out up to full size completes

the picture, so to speak. Results at all scales are consistent,

so this strategy works well on the i9900. The tonalities you

see in a 5x7 match those in a 12x18.

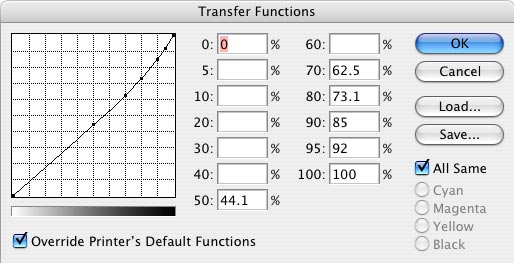

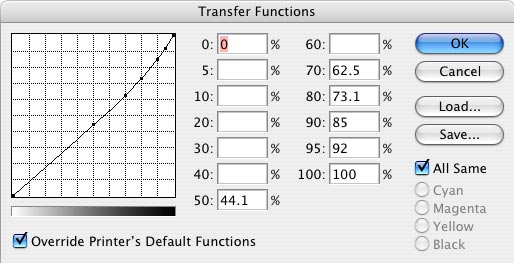

As is typical with any color printer, images

in Photoshop will need to run through either a standardized tweak

to the image or Transfer Function to adjust them to ink on paper

versus the image on the screen. I selected a particularly challenging

shot made with the EOS 300D that contained extremely delicate

highlights, bold and subtle coloration, and very difficult shadow

detail.

Here's the shot:

The light orange float never quite bleaches

out in the shot, and the dark shadow detail against the dark

dock surface and in the shadowed net areas proved to be the hardest

to control, so the question became, will a small custom Transfer

Function in Photoshop do the trick on my Mac? I tried one that

lifted the shadows a little too much, then pulled back to this

one:

Bleached highlights were never a problem,

so the focus of this Transfer Function is all in lifting shadows

up to the level I see on my monitor, and it works. Using this

transfer function on several images produced superior results.

And each print was made at 12x18 on 13x19 paper.

When you make an image that big, people

gasp when they see it. You get a lot of ooo's and aaah's. It's

not uncommon to hear people wonder aloud if the original was

large format film, too. The print from an uncropped full frame

shows up this large with just a fraction over 170 ppi (pixels

per inch) and viewing it closer than you would normally regard

an image never disappoints, in fact it's rather inspiring. I

keep thinking of all those tiny people down there from Bangkok

with their colored hats...

Note: every single paper you use will react

to the ink slightly differently. It's not a Canon thing, it's

just a paper and ink thing, so for full custom print quality

results, you need to get used to the idea of custom print output

settings. Default results are quite pleasant, and the Canon Printer

Drivers offer the option of making a Lighter print for folks

who aren't looking for pro results, but at $2.25 a whack for

the paper, the only thing standing between you and superb output

is the desire to learn that last Transfer Function step in Photoshop.

But I digress...

Where Faded

Ink Is What You Want, or, I'll Be Back

We even found that printing on the back

of some troubling media was practical if the ink color was faded

down.

This takes some added explanation.

Paper backing on premium photographic media

is often strictly not printable. It has light gray paper brand

logos on it so you can flip the paper over and be impressed with

the Canon, Kodak, Epson or HP trademark printed at a diagonal.

Some few formulas are true double-sided, and those are no problem,

but printing on the ones that have all that --let's face it--

advertising on it is a good way to smear up the back of the paper.

Ink doesn't adhere well to this slightly plastic-feeling surface,

because it has zero absorbent characteristics, and any contact

with the image is almost guaranteed to move the ink around and

coat your sleeve or finger. I think the manufacturers do this

on purpose just to be mean, but tell me, how do I really feel

about it. Where were we?

The worst case example of this media (no

names, please, Mr. K) was successfully printed by reducing the

black text to 33%, making the print look tastefully faded back.

Full black didn't work, since the ink had no help in drying,

so it beaded up and stayed wet for hours. But the faded text

worked like a champ, allowing data to be printed on the reverse

side, albeit not at full intensity. It won't turn every page

into double sided media, but it works for notes, signatures and

provenance information.

If you are making fine-art prints with

this machine (a distinct consideration) then printing on the

back is a definitely desirable capability.

Ink fade-proofing is long, but not as long

as pigment inks. It's measured in decades and joins a growing

number of printer/ink/paper combinations that are worthy of fine

art production.

There are faster printers for straight

pages of text. But there are no better looking photographic printers

out there. Critics from all sorts of places have recognized the

sheer image quality of this machine. If you need wholesale black

text output, get a laser printer. That said, the text from the

i9900 is as clean as you would wish to see.

Heady Stuff

Print heads are a problem. They can clog,

rendering the printer useless for the moment, or in extreme cases,

forever. HP printers change the print head out with every cartridge,

but neither Epson nor Canon do.

Epson printers are notorious for head clogs,

but most clear out by squirting a quantity of ink through them

in a recovery procedure. If you use them every day (and I do

not) then head clogs are extremely rare. Over time, I imagine

that more than a hundred dollars worth of ink and many hours

of my time have been spent on bringing Epson printers back to

life. One died of terminal head cloggitis and had to be put down.

The Epson factory reconditioning of the old beast would have

cost far more than a newer low-cost model. Such is life and death

in Ink-Jet Land.

HP printers have always been the paragons

of reliability and seem to print perfectly even after months

of sitting around idle. I can't remember the last HP head clog

and I don't know if it's the head design or frequently updated

heads, but it works.

Canon has done the next best thing. You

can interchange the heads for new ones and replace them all in

the privacy of your own home or office. So far, though, the reliability

and clog-free qualities of the i9900 are as good as the HP. I

wish my Epsons had been as good as this.

B and/or W

A big test of a color printer is its performance

in monochrome. We've seen how ugly B&W images can be from

a printer that doesn't *quite* handle all tonalities with equal

freedom from color phenomena, but I'm happy to report that the

i9900 rises to the challenge. Here's a printer I think Ansel

Adams would have enjoyed. Subtle tints and toning also come through

with accuracy and subtlety.

Bottom Line

You have a 5+MP camera and you want the

best results. You want a printer larger than letter size or legal

size to deliver the results your camera actually captures, so

you want something this size. For the Digital Rebel or 20D or

EOS 1Ds --or anything else that requires tabloid size color print

outs-- the i9900 fills in all of your wants except the one that

says, "...and it should cost me under a hundred bucks."

This isn't a cheap printer, but it goes head to head with $700.00

printers, though, and comes up costing just over half of that.

If I had to pick between an Epson Photo

2200 and the Canon i9900 all over again, I'd pick the i9900 and

save a chunk of hard-won cash.

Understandably, Canon is proud of their

latest printer technologies and there are a host of them you

can read about here.

From a performance standpoint, this would

be the printer worth saving up your nickels and quarters for.

It's a stretch to buy a printer this expensive, but your digital

camera cries out for expression and where it comes to printing,

this one is the most expressive.

You can find it around the Web for about

$400US and if your experience with it is anything like mine,

you won't regret the purchase for an instant

Canon i9900 Printer: A+*

Other Reviewers:

Imaging Resource

Steve's Digicams

PC Magazine

PC World

Canon's

i9900 printer has carved out a special place in the hearts and

minds of digital photographers --and even hold-out film photographers--

everywhere. The reason for that has to do with its sheer image

quality and performance. It's fast, silent, easy to work with,

and the pictures it produces are beyond criticism.

Canon's

i9900 printer has carved out a special place in the hearts and

minds of digital photographers --and even hold-out film photographers--

everywhere. The reason for that has to do with its sheer image

quality and performance. It's fast, silent, easy to work with,

and the pictures it produces are beyond criticism.

For

your Canon Digital Rebel- DSLR: Canon Digital Rebel EOS 300D

eBook is already on the shelf. DSLR: Canon Digital Rebel XT is

next. Then DSLR: Canon 20D follows. These are great cameras with

a great deal inside them, so we put a great deal of information

into their eBooks. You'll find things here that nobody else ever

told you about and not even Canon knew or could discuss.

For

your Canon Digital Rebel- DSLR: Canon Digital Rebel EOS 300D

eBook is already on the shelf. DSLR: Canon Digital Rebel XT is

next. Then DSLR: Canon 20D follows. These are great cameras with

a great deal inside them, so we put a great deal of information

into their eBooks. You'll find things here that nobody else ever

told you about and not even Canon knew or could discuss.