|

Equipment reports here are evolving documents. Return visits may reveal more information. Latest update: 4/1/09 |

You Got to Move It Move It When Is a Still Camera Not a Still Camera? When it Movies. What we knew before we handled the camera: We hoped that the Big New Feature of the Nikon D90 would turn out to fulfill or overflow the hype. You probably already have heard endlessly how it shoots movies. 24 fps, 720p, meaning a decent high-definition image that covers 720 x 1280 pixels per frame, saved to its SD card at a rate of about 500 MB/minute in AVI format. Now we set out to run the D90 through our pickey, pickey, pickey analysis. We have speculated in the past why DSLRs didn't evolve faster frame rates, eschewing the mirror flaps per shot, and now it seemed to be here. If the D90 were to shoot great 720-line, 24p imagery, it could become a wonderful addition to the digital camera universe. Fox Network distributes HD as 720-line material, not always 24p, but in practical terms, a great looking HD image. RED camera has built supreme motion picture cameras around a similar-sized (APS-C) "Mysterium" image chip, not more than a very few mm different from the size of the 4K image chip in the D2x, D300 and now D90 cameras.

RED cameras sweep every pixel off for each frame in RAW form, extending the frame rates to 30 fps and even 120 fps with images down-sampled to 2048 pixels wide. Clearly they are way ahead of the curve when it comes to deriving cinematic images from single chip sensors, but the question in our minds was "Will the D90 show a tendency to rise into this realm from the bottom up? Will it produce pro-level 720p images?" Eventually, DSLRs for stills will be able to shovel much higher frame rates, much bigger images and much greater dynamic ranges off of their image chips than the D90 achieves, but for now, it could be the smallest, lightest theater-ready movie camera around. Potentially. While Canon and Sony relentlessly pursue 14 MP, 16 MP, 22 MP, 25 MP and beyond image chips, they are running into several walls. Diffraction, for instance, maxxes out in the DX image chips of 12.x MP Nikons at f/9. Would this be a factor in a 720p movie? The answer to that is something you can calculate instantly. No, diffraction would be limited to 1/1280th of the image width, which is a known 23.6 mm. Or in other words, the airy disc of diffraction would be 350% larger than it would be for stills shot at 4288 pixels wide. Put into practical terms, a D90 movie image can get away with f/23 and not show diffraction-limited sharpness. Movie Quiz The central question at this moment, is nothing I've seen in other speculations about D90 video mode. Instead, it has to do with HOW dense image chips are used as viewfinders. Early pocket cameras started shooting movies as soon as designers realized that their live viewfinder images might just as well be recorded. Recordable video started as something of a novelty, then grew to "video definition" and has been carried all the way up to the Casio EXILIM Pro EX-F1, which can inhale its 6 MP images at a considerable 60 frames per second. For one second. When you lower the image size, the number of seconds of Casio recording go up and up, all the way to small images of 336 by 96 pixels at 1200 frames per second. The EX-F1 also records full 1080i HD at 60 fields per second. But the image chip in the EX-F1 is small, "1/1.8-inch format", pocket camera size, with deep DOF, diffraction limits based on small airy disk size. Still images are diffraction limited at f/4.1!!! But what many people may have missed is this: The WAY a big, multi-megabyte image chip pulls its image from the chip is nowhere near obvious and simple. And it is strictly NOT the way any dedicated high-definition video camera achieves its picture. If I hadn't studied the tech specs of the image chips for pocket cameras, I probably would have missed it too. Many viewfinder live video images are the product of sampling only selected photosites. It skips pixels across the face of the image chip when it inhales live images. I'll let that sink in a moment. Most photosites with most of the available still/video cameras, when shooting as video mode, are entirely ignored. It's not like every frame starts its life as a RAW scan of the chip (the way the RED camera does it), then becomes crushed down to video size. The image chip is designed to routinely enter into a special Viewfinder Mode which can be any of a number of schemes that skip pixels and scan lines, thus severely compromising live image quality in the service of fast viewing. By targeting a spread-out pattern of specific photosites as fast-reading video feeds, pocket camera viewfinder requirements are met, but those images are not representative of what the final definition of the image will contain. Most often they have severe edge definition "issues" and look lower in quality than a low-cost video camera. Why throw away pixels to shoot video? If an image chip that was only fast enough to capture, say, 5 frames per second were to only poll 1/3 of horizontal and vertical photosites, it would improve the reading speed by 900%, effectively turning a still image chip into a live video chip that could theoretically capture 45 frames per second. Each frame would only have 1/9th the detail of an all-pixel still image, but the whole image chip's field of view would be represented. And that's just one scheme from the past. The problem with those images is that fine detail can fail to show up if it falls between the live photosites, causing edge definition artifacts. Nobody gives a rat's if the live viewfinder image has artifacts. Live viewing is just a convenience—a way to find the view. When you want to record it as a high quality moving image, the stakes go up and expectations can run wild. Rude Awakening? Prior to working with the D90, we didn't know that this was happening in D90 video mode, but we knew that if it were, we might be bummed out in a major way. What we WANTED it to do is generate perfect 720 x 1280 x 24 fps images in a way that can be captured and used for anything. TV shows, for instance. B-roll image capture, for instance. Stock shots for instance. Because the big 12.2 MP still image can meet and compete in all the still-image arenas that parallel these notions. The D90's still images are fully professional and usable for virtually all sorts of thoroughly pro jobs. Would D-Movie mode live up to the professional expectations of the still mode? Demo-goop The Nikon Website's first official D-Movie demo seemed somewhat contrived.

If the actual resulting images were true down-converted 4288 x 2848 full image chip sweeps that have been packaged at 720 x 1280, then compressed, they should be gorgeous. If not, we feared they could be somewhat compromised and professionally unusable. We would hate to see such a feature relegated to the "So Near, and Yet, So What" category of feature novelties.

Along with the announcement of the D90 came this oft repeated sentiment: "Nikon has no experience with moving images," and variations of that blah blah. Not true. Apparently none of today's living journalists ever held a Nikon Hi8 video camcorder (VN-760, VN-960) in their hands or previous Nikon Super 8 film cameras (R8, R10, pictured). Actually the Nikon-branded video camcorders from the late 1980s were made by Sony. I know this for certain. I had five of the Nikon versions and one of the Sonys, and all of them were part-for-part identical in every respect. Everything but the exterior graphic markings was the same. I directed a project in Canada that sent the Nikon Hi8 camcorders over Niagara falls in windowed high-tech waterproof barrels. We also sent them down the Niagara rapids, and made a simulator ride experience from the results. It worked, and they worked. (One of the Nikon barrels hit a major rock at the base of the falls, bounced sideways, lost water seals and still delivered its unique image into the show. An inner waterproof bag helped, but the tripod screw connection plate was bent 90 degrees. Still, after it dried out, it continued to function as a playback camcorder.) Back in the day of Super 8 movies and Double-8 movies, Nikon had numerous models that earned various degrees of respect. Also, many of their compact cameras have enjoyed movie modes, video modes and motion options, so on the face of it, one can say that Nikon has a particular level of motion experience. Not as much as Canon or Sony, however.

Do we like the D90? Executive Summary: 1. What part of "At the end of the day, a sea change is coming out of left field" don't you understand? 2. The future is so bright that lens shades are mandatory. 3. We like the D90 a lot. It's one of the very best still cameras we ever ate, and except for a short list of features, its movie mode does things you just can't do with even a $120,000 HD camcorder. 4. This is Gen #1 of a string of evolutionary improvements that will deliver a Panavision studio camera into your hands within three years for 1000 small ones. 5. There's already rumor talk of a D400 with 1080p 24 or 30 fps movie capture. We Shell Sea. 6. I don't see many people shooting major motion pictures on it tomorrow afternoon, but it blurs the definition of what's-a-camera so much that it is impossible to dismiss it. 7 through 10. Absolute bottom of the bottom line: Get one and start learning how Hollywood movie shooting is way different from camcorder shooting. Even with its limitations, the movie scenes can be stunning. What We Found With the D90 In Hand: We fired up the D90 in movie mode (easy; just press the OK button during Live View, which has its own handy dedicated button) and started making movies. On the camera monitor (which is the ultra-definition 3-incher found on the D3 and D300) everything seemed fine. Or was it? Not quite. Panning around slowly, we noticed immediately that exposure during video mode—jumps. As the camera senses light and dark changes in the image, exposure lifts and drops in quantum steps—not the smooth changes that any video camera would naturally produce. (Sure, there may be some video cameras out there that don't do this smoothly, but you get what I mean.) We suspect that these steps are 1/3-stop jumps, but they may be a smaller amount. In any case, they are discrete exposure changes so you would have to lock exposure to avoid them. That's not so bad, most pro video is shot with exposure shutter speed and aperture locked during the shot.

No control is offered for shutter duration. You can't just dial in a 1/48 sec shutter speed for true 24p movie-like motion blur. Worse: The D90 has a "rolling shutter" effect that scans the image off the chip from top to bottom taking about 1/24 second for each frame, creating a severe focal plane shutter distortion effect that hasn't been witnessed since the days of cloth focal plane shutters that moved relatively slowly. (Canon bowed to user pressure and endowed their EOS 5 Mark II with manual exposure adjustments via a firmware update. While this is a sane and smart thing for them to have done, it may not be technically possible for the Nikon D90. But if it is, then Nikon should do it in my opinion.) Even when the effective exposure is 1/1000 sec or so, the time it takes to scan it off the image chip follows a sequence that distorts subject matter when the camera pans or tilts quickly.

Focus can be obtained during the Live View preview before triggering motion capture. Outdoors in full sun, this is an exercise in futility. I can't see the screen! Some help will be needed to shade the camera monitor down to viewable level, and although the camera can help a bit (Live View has an image brightening option), it's not enough for sunlight on the camera. Hoodman to the rescue. In nominal light indoor or in shade, after focus is obtained, shooting video while viewing the camera monitor is fairly easy. It's a better monitor than the one on my two dedicated HD cameras. If you have to change focus during the shot, manual focus is your only option. Setting up and rehearsing multi-focus and follow focus shots is required.

As we had anticipated, the D90 skips pixels in movie mode, leading to a unique set of visual artifacts that may or may not be noticed by viewers. Ouch. It compromises detail—especially fine horizontal detail and contours. This will always be a nomenclature problem: Horizontal detail in my jargon means fine horizontal structures, and compressing horizontal detail means crushing it vertically. Not squeezing it in the horizontal plane. Also, in this case, compressing means squishing, not reducing the file size.

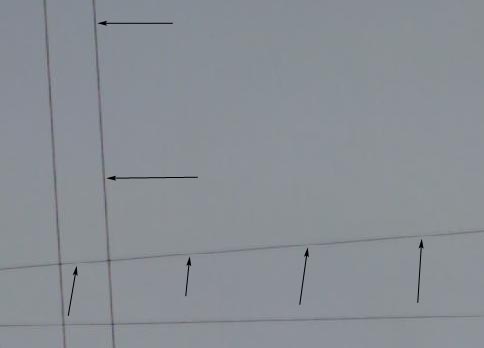

Artifacts in the scene show the effect of a fast scaling engine, quite similar in appearance to Photoshop's Nearest Neighbor scaling engine applied to a graphic. The advantage to such an approach would be the use of simple, fast computing integer math. Something that 24 image computations would benefit from. Some of the common math of camcorders may be at play. An undocumented feature of the D300's RAW image showed how that camera could produce images wider than the 4288 pixels of a Large frame. It's not much of a stretch to imagine that the image chip in the D90 might capture 32 more horizontal pixels for D-Movie frame use. Here's how that may work: Many HD camcorders expose an image with 1440 photosites in each row of their image chip (later stretched by 133% to 1920 pixels), and a relationship of 1240:1440 is exactly an 8:9 ratio. The vertical result of this sort of scaling (810 scan lines converting to 720 for the 16:9 HD image) might be what produces the artifact every eight pixels, top to bottom, in the D90 video image (as in the shallow horizontal line in the illustration at right). 1440 is exactly 1/3 of 4320 pixels, and the image chip--not the still image that it produces--has more than that many on its face, side to side. Nikon isn't saying exactly what is going on in achieving its 720p image, but one thing can be seen directly: Vertical lines don't show a scaling artifact, perhaps because the whole horizontal row of photosites is involved in sampling the image. Maybe only the vertical scan line relationship receives the accelerated math routine?

The image is scrolled off the image chip from top to bottom, then repeats in a scan-line like sequence. It looks like a slow, but narrow focal plane shutter effect. It's going to turn vertical features into angled features in the scene if you pan fast enough. There is no remedy for this, but there are ways of avoiding it as an obvous scene-stealer. Compression artifacts are visible in still frames shot with Small / Basic JPEG format (and not always), but tend to become lost in motion scenes. No contour-hugging artifacts show up at all. An original published spec said 500 MB/minute. Nope. Try 100 to 175 MB/minute, depending on scenic content. That's reality for real world scenes. Audio is not controllable directly. Auto gain and auto compression are on all the time. Here's a suggestion we used when shooting far from a subject that was issuing audio we wanted to capture: Shoot double system. That means have a recording device near or on the subject that is distant from the camera, then replace the D90 audio with the closer recording audio in editing. It's done all the time in professional video and movies. MP3 devices with on-board recording capabilities suddenly take on a whole new role. Once again, my iPhone has become more useful.

Getting the Most Given the constraints of the D90 movie mode as it sits, what can you do with movie mode on the D90? Shoot in ways that don't exacerbate the artifacts. Things it does right include all the Set Picture Control settings. Meaning that Contrast, Sharpening and Saturation are available to the setup of your shot. You can shoot Monochrome and tint the output into numerous color effects. With a concert of settings, you can tweak the in-camera image into pretty good stylistic looks that imitate Hollywood's more interesting movie visual treatments. A chart for obtaining a bunch of different movie "looks" is in the eBook. For creating HD materials for the Internet, the D90 is a major useful tool. Combined with the right editing programs it can achieve exceptional results. The D90 eBook has numerous examples of hight-impact movie shooting and editing techniques that are accessible with low-cost software. Active D-Lighting is ignored. Color Space is ignored. Dang. D-Lighting could have been cool. EV± works to dim or brighten the scene but the auto exposure jumps stay active. With Capture NX, you can shoot using custom curves and possibly get a more film-like tonal effect.

—Peter iNova Peter iNova is a photographer who remembers film, enlargers, slides, darkroom stains and all the things you don't have to. His checkered career has included big studio photography (8 x 10 transparencies) in Chicago, video production in Florida, and exotic multi-projector synchronized video presentations for Universal Studios, National Geographic and theme parks around the world. At one time racked up over a million dollars worth of film stock and lab fees, commenting, "Geez. We have to find a way of doing this with computers." He is the prime inventor of a number of patents in extreme video display technologies. When digital cameras passed the million pixel threshold, he turned once again to still photography and created the first interactive digital photography eBook in 2000. His experiences with video are a match with the emerging talents of what he calls HDSLRs.

|

|

9/20/08 (new)

9/20/08 (new) Press Misses

Press Misses While we have no technical confirmation of this, we think it literally drops 2 out of every 3 photosites during exposure, building an internal image that is 14xx-ish pixels wide by 8xx-ish pixels tall, then crops that and scales that image, on the fly, down to 720 x 1280.

While we have no technical confirmation of this, we think it literally drops 2 out of every 3 photosites during exposure, building an internal image that is 14xx-ish pixels wide by 8xx-ish pixels tall, then crops that and scales that image, on the fly, down to 720 x 1280.